By Melissa Sirois

“We’re freaking slammed everywhere—all over the culture and all of these billboards, commercials, everything! But then the minute it gets down to the real thing, no one wants to talk about it.”

So said Lilly Bosco, a member of Plainville High School’s graduating class of 2012 and a marketing student at the University of Hartford. She’s in the middle of her commute to school on a Sunday afternoon, and there is no hiding the fact that she is frustrated.

But it’s not the extra hours at the library that have got her speaking so passionately—at least, not this time. It’s the issue of the current state of sexual education curriculum in Connecticut.

But it’s not the extra hours at the library that have got her speaking so passionately—at least, not this time. It’s the issue of the current state of sexual education curriculum in Connecticut.

Bosco says the system has not provided a comprehensive sexual education experience for students in middle and high schools. And she’s not alone in her opinions.

In 1987, the Center for Disease Control introduced a system for integrating health education practices into school settings across the United States. The approach, called “Coordinated School Health” (CSH), established the goal of improving the health of students in the hopes of also improving academic achievement.

According to the Connecticut Department of Education, the CSH blueprint is applied in partnership with support from the Department of Public Health and funding from the CDC. The DOE’s mission statement for the approach is “to nurture the physical, social and emotional health of the entire school community…and to promote and support the full implementation of a coordinated approach to school health…”

Connecticut’s sexual health education curriculum’s eight content standards, in line with the CSH program, include items such as “analyze factors that may contribute to a healthy and unhealthy relationship” and “discuss important health assessments, screenings and examinations that are necessary to maintain reproductive health.”

While a 2003 study sponsored by Advocates for Youth and The Parisky Group of Hartford showed 91 percent of all adults support sexual education in high school, some of the people most affected — students and their primary care providers — say not enough is being done to create an integrated approach to sexual education in the classroom.

Michael Corjulo is the former president of the Association of School Nurses of Connecticut and a pediatric nurse practitioner at the Children’s Medical Group in Hamden. He believes people at the DOE have good intentions and would probably be open to more collaboration with parents and primary care providers.

“I think the important thing is that we make a structured effort to try to ensure that we’re giving kids the same message about sexual education in schools as they would get by their primary care provider,” he said.

Bosco supports this notion, too. She said the education system should be more in tune with students’ sexual educational needs, which include the knowledge of resources and more transparent discussions around how to have consensual, safe, fun sex.

Of her sexual education experience in Plainville’s public school system, she said, “I don’t remember anything too significant…. I don’t think it was really taught in an effective way. They just wanted to get through it with us.”

“There was never any followup,” she said.

According to Corjulo, Bosco and thousands of other students like her have experienced a superficial approach to sexual education.

Statistics from the Connecticut School Health Profiles (SHP) for 2010 illustrate the discrepancies in sexual education curriculums. In 2010, 87 percent of health courses in grades six through 12 taught about HIV prevention; 88 percent about human sexuality; 78 percent about pregnancy prevention; and 87 percent about STD prevention.

That same year, 95 percent of high school sex ed teachers and 75 percent of middle school sex ed teachers taught abstinence as the best method of avoiding HIV infection.

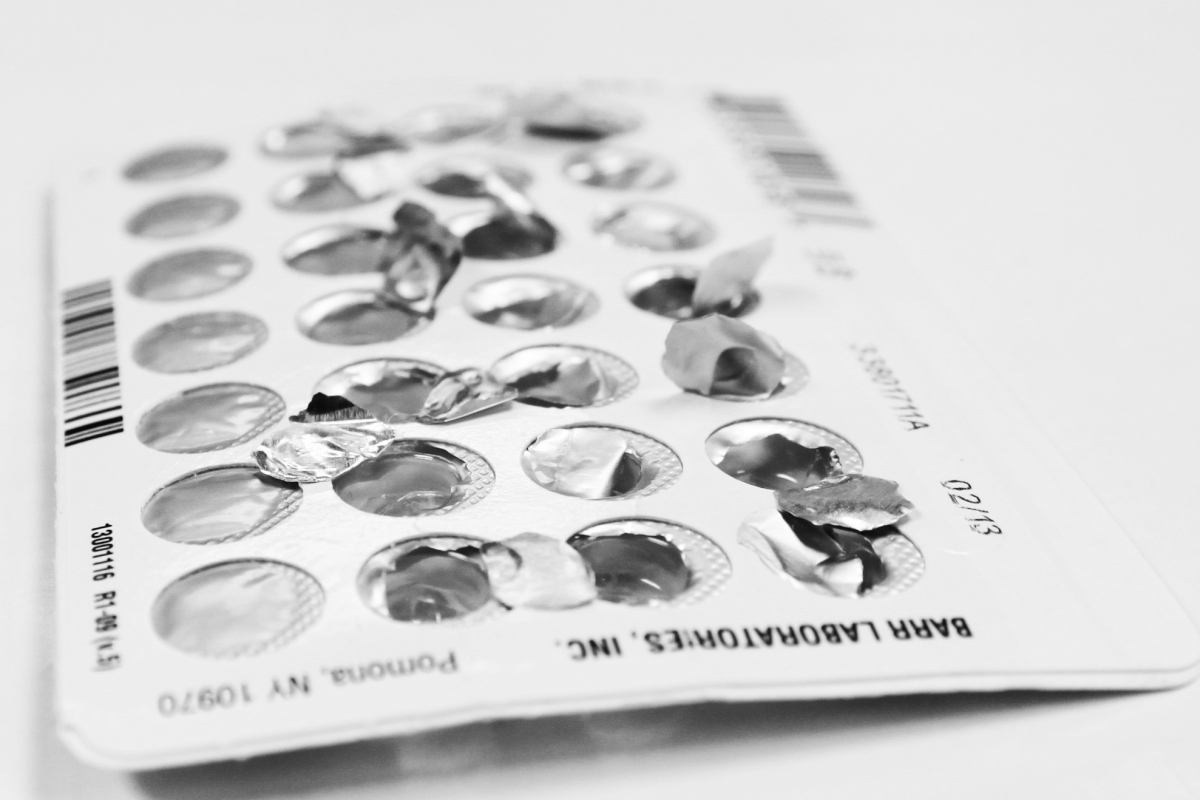

By comparison, the report said educators were “less likely to provide instruction on ‘controversial’ methods.” For instance, 66 percent of teachers instructed on the importance of using condoms consistently and correctly, and only 56 percent taught students about how to obtain condoms.

Emma Bartley also attended junior high in Plainville, but spent her high school years at St. Paul Catholic High School in Bristol, where she graduated in 2015. She had a bit of a different experience as she moved from public to private school.

Bartley said she was exposed to sexual education in religion class at St. Paul under a faith-based approach, where she felt educators didn’t address the reality of the situation.

“They weren’t telling us what to believe — they would say, ‘Use protection,’ but I feel like at the same time they kind of acted so innocent and just acted like we were all waiting until marriage,” she said. “They were almost blind to what was actually going on, but they wouldn’t admit it.”

To be fair, Bartley said she feels as though St. Paul’s health curriculum generally worked pretty well for her. She learned the ins and outs of harmful drugs and alcohol, and she said there was a lot of focus on building healthy relationships and recognizing unhealthy dating practices.

Bosco said she sees obvious room for improvement and places blame on the overarching taboo culture surrounding sex — the one where sex sells, but we’re afraid to talk about it with our children.

“I think it really starts with kids, and they’re not having the proper conversations,” she said. “It’s totally being brought to them in an awkward way right from the beginning — that it’s weird, and it’s not a normal conversation [to have].”

On the awkward conversation front, Corjulo would agree. He said while some schools across the state probably handle sexual education very well, “It’s sort of hit or miss. It’s not a structured, intentional approach.”

A lot of this, he said, stems from unprepared faculty members — gym teachers, for instance — who are unaware of how to broach the topic with their students. “I don’t think that health educators in schools get down to that level of, ‘OK. You’re in this situation here…’,” he said.

Both Bartley and Bosco said they didn’t experience truly open conversations about sex until college, where free condoms are often distributed in student centers, and there are semester-long courses dedicated to discussions of human sexuality.

During her freshman year at University of Hartford, Bosco had her own sexual health scare, something she says high school health class did not prepare her for but should have.

Before she knew it, an STD had passed through three unknowing people, and she was one of them. Bosco said she was infected for three months before she even realized something was wrong and found the courage to ask for help.

“The dangers of sex that exist — they’re real. But they don’t have to become part of your sex life,” she said.

Melissa Sirois is a senior journalism major at Quinnipiac University. She is writing about public health this spring. She can be reached at melissa.sirois@quinnipiac.edu.