By Julia Perkins

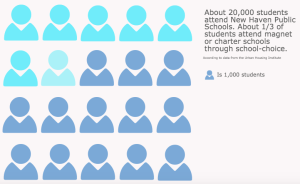

Elm City Communities, formerly called the New Haven Housing Authority, is working to close the achievement gap in New Haven public schools through a program called “Elm City Believes.” Under this program, the housing authority works with city schools to provide educational services for students living in public housing. The initiative was highlighted in an Urban Institute report last year, and Elm City Communities Education Policy Director Emily Byrne said this idea has the potential to be a model for the rest of the country.

Q: How did Elm City Believes first kick off?

Emily Byrne: “Public housing authorities have been serving the nation and working class families for a long time, and their educational systems have been working to educate children for a long time. And one of the big challenges for housing authorities has been to solve poverty and one of the big challenges for education systems is to close the achievement gap. But it’s very rare for these institutions to come together and collaborate in any work. It makes complete sense, but it’s very rarely done. When I started at the New Haven Housing Authority, Elm City Communities, my position was actually one of the first in the country that was at the intersection of housing and education, and I think since my time, my being hired here, many more housing authorities across the country have roles similar to mine and are doing this work, which is really at the forefront of a movement to break down silos between housing and education.”

Q: What is that connection between the housing side and education side?

EB: “Both schools and public housing authorities are serving the lowest-income children.”

Q: Can you talk about what Elm City Believes does for students in New Haven?

EB: “The initiative is for youth in grades K-12 who call public housing home. The idea is for the public housing authority to serve both as a platform and a portal in that it would form partnerships with local schools or school districts as well as community-based organizations.”

Q: And in those partnerships, what happens?

EB: “The main goal of Elm City Believes is to close opportunity gaps for low- and no-income New Haven families in order to close the achievement gap …. stopping generational poverty.”

Q: How does that help to stop generational poverty?

EB: “Our theory of change is really around that our serving as a platform and portal and connecting students and families with the resources they need to be academically successful will increase their academic achievement, will increase high school graduation rates, increase post-secondary completion, and eventually that leads to employment attainment and then ultimately end generational poverty. So as a housing authority [Executive Director of Elm City Communities] Karen [DuBois-Walton] says this all the time, as a housing authority, we will always be in the business of housing, but we shouldn’t be in the business of housing the same generation of families.”

Q: Obviously the needs of the younger students are going to be different than the needs of maybe students who are in high school. So how do you go about making sure the students of different ages are getting the resources they need? How is the program different for someone who is in Kindergarten versus someone who is in high school?

EB: “The program is really retail in that the way we designed it is based around data sharing agreements and memorandum of understanding with either a school district or an individual school. Once those agreements are signed, it allows us to work with parents to sign consent forms so that we can see the needs that each child has. So within any one school, the needs of the children that are in that school that happen to be our residents could vary dramatically.

“You’re raising the point of younger kids versus older kids, and I think for us that’s illustrated the best within the ways the schools are structured. New Haven is a magnet school program. Several years ago they moved into a structure where the schools are K-8 and high school. So, for example, a Pre-K or K-8 school, particularly for the kids that are in second grade or lower or third grade or lower, we would be working with not just the kids, but with the parents, too. So, for example, let’s say you’ve got a second grader who is missing school on a regular basis. The reason for that child missing school on a regular basis is very different than if it were a 10th grader missing school on a regular basis, most likely. Because for a 10th grader, we would probably go directly to the student and say ‘why did you miss school,’ because they’re older, there’s a little bit more of a choice to attend or not attend school. We’re placing the onus most likely on the student. Whereas a second grader can’t walk to school by him or herself, the choice really isn’t hers or his … So then it’s a matter of asking the parents, what can we do to help you get your children to school with fidelity. Is it an issue with transportation? Is it an issue with walking on time because you’re working multiple jobs?”

Q: Can you talk about the impact the program has had on students in New Haven so far? Like, have students been getting better grades or going to school more often? Has there been an impact on graduation rates yet?

EB: “We’re only in our second full year, second full academic year, and I think it would be pretty early to make a determination on whether the program has been successful or not, but from early stage data points, students are doing better academically. Students are attending school more and families anecdotally are saying they feel more supported so this is all a good thing.”

Q: What have been some of the challenges you have faced in implementing and carrying out this program and how have you guys worked to overcome those challenges?

EB: “I think one of the concerns that we had initially before launching Elm City Believes was whether or not parents and families would be receptive to the housing authority doing this kind of work. We are effectively their landlord. We’re the largest landlord in the City of New Haven, and housing authorities across the country don’t do this kind of work, right? They’re objective is to house people. We believe that housing authorities should do more. For us, I think we fundamentally believe that public housing the foundation from which the American Dream can survive for generations to come. That’s language that we use because it’s so connected. There’s good data on how connected it is to people succeeding in careers, people being self sufficient and so I think for us our big concern was to what extent are people going to be open to them. Fortunately, I think the response from a lot of our residents is ‘it’s about time.’ They were waiting for us to do something, which is a great thing, but it shows that there is a need and the need that is probably illustrative of the need nationally, but nationally they’re probably aren’t the kind of resources we have.”

Q: How does Elm City Communities get the resources to be able to have this program?

EB: “We are HUD designated Moving to Work agency. HUD is the Housing Department of Urban Development, and Moving to Work is a status given to 39 housing authorities throughout the country. It was started during Clinton administration and it doesn’t allow for more federal dollars into the housing authorities that have this status, what it does is it allows housing authorities to use their funds flexibly.

“The idea was that not all public housing authorities are the same, and that so the one-size-fits-all approach isn’t the best approach. Moving to work was created as a demonstration project to these 39 housing authorities to develop policies and programs in a manner that the agency felt best served the community and best served the needs of the residents they were housing.”

Q: What are your future goals for the program?

EB: “I think the vision is in New Haven that every child has equal opportunity to fulfill his or her dream. I think for us part of the reason why we launched Elm City Believes is because we think that’s a step toward that direction.

“I genuinely believe that housing-education partnerships and partnerships that fall in the intersection of issues is the future.”

Julia Perkins is a senior journalism major at Quinnipiac University and is editor-in-chief of The Quinnipiac Chronicle. She is writing about poverty and income inequality this spring. She can be reached at julia.perkins@quinnipiac.edu.

But it’s not the extra hours at the library that have got her speaking so passionately—at least, not this time. It’s the issue of the current state of sexual education curriculum in Connecticut.

But it’s not the extra hours at the library that have got her speaking so passionately—at least, not this time. It’s the issue of the current state of sexual education curriculum in Connecticut.