By Julia Perkins

Shelters and organizations in the New Haven region say their efforts to end homelessness are working, despite the poverty in the area.

There are many different reasons someone could become homeless. Mental illness, substance abuse, a tragedy such as a fire, or release from prison are all factors that contribute to homelessness, New Haven Emergency Shelter Management Services Executive Director Arnold Johnson said.

“There’s no one reason [for homelessness,]” he said. “I joke around all the time and say we’re all maybe two paychecks away from being homeless.

But poverty is often a big reason, said Alison Cunningham, the executive director of Columbus House in New Haven and Middletown. The cost of housing is high, she said, and a single adult could have to pay more than $1,000 a month for an apartment.

“Well if you’re disabled and on Social Security, you might get $703 a month, so do the math it doesn’t work,” she said.

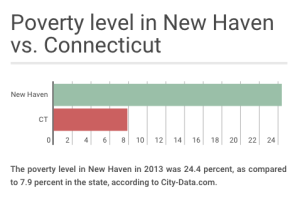

New Haven was ranked No. 6 on a list of American cities with the greatest income inequality in a Brookings Institution study. About 24 percent of New Haven residents lived below the poverty level in 2013, as compared to 7.9 percent in the state, according to City-Data.com.

Yet, Connecticut recently announced it ended homelessness among veterans and has made it a goal to put a stop to chronic homelessness by the end of 2016. The number of homeless people in New Haven in 2015 has decreased by 9 percent since 2011, according to the Coalition to End Homelessness’ Point in Time count.

Liberty Community Services Executive Director John Bradley said this is because homelessness organizations in the state are getting more funding and collaborating more.

“Homelessness is a problem in the United States and Connecticut, but it is something we can do something about,” Bradley said. “New Haven, Connecticut and generally most parts of the country have seen a decrease in homelessness over the last couple years, which is not insignificant because we’re living in a time where housing prices are going up and income inequity is going up, but we’re still making progress on ending homelessness because we know what works.”

Bradley said one system that has been working is called the Coordinated Access Network (CAN).

This program was started in 2014 after President Barack Obama passed the Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing (HEARTH) Act of 2009. This legislation required organizations to work together so that no one is homeless for more than 30 days and people do not return to homelessness, according to the Coalition to End Homelessness.

Under CAN, the state is separated into eight regions, and organizations pool their resources to get people into housing as soon as possible.

“It used to work that anyone who qualified for permanent supportive housing would put their name on the application of each individual agency,” Bradley said. “So that if we had an opening we would serve them, but if we didn’t they would go on the wait list of another agency. So that’s all changed now so that we’re coordinated, and no matter where the person comes in, they get access to the resources of the entire community.”

Everything is streamlined now so that there is one universal housing list, Cunningham said. For example, if someone calls United Way’s hotline for the homeless, 211, he or she would then meet with a coordinator for an assessment, get a shelter bed and then be put on the list.

The Greater New Haven region has gotten better at reducing the amount of time between when one calls 211 to when the person has an assessment to determine his or her needs, according to data from the Coalition to End Homelessness. From January 2015 to June 2015, the average wait time for an appointment was 28 days. This decreased to 12 days from July 2015 to January 2016.

A CAN specialist then works with the different organizations to see who has available subsidies that meet that person’s needs.

“That’s a great thing because that means we put all of our housing in a big pot and say here it all is and let’s just make sure the person comes up on the list to the very next available unit,” Cunningham said. “It’s a different way of doing business, and it’s worked very well to move people off that list very quickly.”

Julia Perkins is a senior journalism major at Quinnipiac University and is editor-in-chief of The Quinnipiac Chronicle. She is writing about poverty and income inequality this spring. She can be reached at julia.perkins@quinnipiac.edu.