By Melissa Sirois

Perhaps it wasn’t being practiced or talked about in decades’ past, or perhaps it was still in the process of being socially constructed, and we hadn’t come up with a name for it yet.

Either way, it didn’t appear as prominently in the public sphere. Today, though, “mindfulness” is everywhere.

It’s on the New York Times’ Best Sellers list in the form of Dan Harris’ 10% Happier, a story of the Nightline co-anchor’s experiences with meditation. It’s practiced and praised by everyone from Anderson Cooper, to Katy Perry, to Derek Jeter. It’s even being implemented across Silicon Valley at tech giants such as Apple and Google.

But what, exactly, is mindfulness? And why do people care?

The Capitol Region Education Council (CREC) out of Hartford promotes mindfulness as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally.” Essentially, mindfulness is being consciously and acutely aware of your senses and living in the present moment, away from the usual distractions.

Emily Rosen is an educational technology and mindfulness specialist at CREC and has been working in the world of mindfulness for 12 years. She said the practice is about learning how to disconnect and take a pause.

“You could be mindful about anything,” she said. “You could be mindful about doing the dishes. It’s a question of putting your mind and your senses and your attention all in one place.”

Jennifer Berard, chair of Pratt & Whitney’s Military Engines Health and Wellness Committee, echoed this sentiment — that mindfulness can be practiced anytime, anywhere, even while doing things that may seem mundane.

Berard said that people who are truly happy live in the present moment and appreciate it for what it is. She sees a need for increased self-awareness, especially among people in the corporate working environment. “You’re spread across thin,” she said. “You’re in the past, and you’re in the future. You’re not in the moment.”

Both Rosen and Berard stressed that mindfulness is more than just meditation, yoga and breathing exercises. Rather, mindfulness is the larger umbrella that encompasses these tactics, and it is a skill that manifests itself differently in people.

The practice of mindfulness is not only helpful for short-term focusing and attentiveness. Extensive research by neuroscientists has documented that consistent mindfulness practices can result in increased feelings of calm and empathy for others, improved impulse control and emotional regulation and decreased levels of stress, anxiety and depression.

Historically, psychologists have used mindfulness as an approach to therapy for those who have experienced emotional trauma and extreme, prolonged stress.

Rosen said that mindfulness is different than the traditional approach to therapy, “but it’s kinder and gentler in some ways. It’s a process. It’s not a quick fix for sure.”

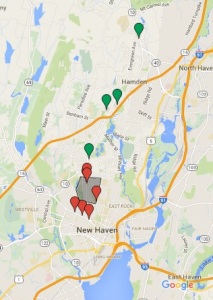

New Haven Insight is a meditation community that hosts group sessions every Monday and Thursday evening in the Dwight Hall Chapel on Yale University’s old campus. According to an informational brochure, the group, founded in 2008, is “dedicated to the practice of mindful awareness and compassion with the goal of decreasing (and ending) stress and suffering for all.”

Connecticut is also home to the mindfulness retreat center that is Copper Beech Institute. Based out of West Hartford and founded by a University of Notre Dame alumnus, Copper Beech offers daylong and overnight retreats, meditation groups, mindfulness education courses and workshops with mindfulness experts.

According to its website, “Copper Beech Institute envisions a future where mindfulness and contemplative practice are transforming education, health care, business, government, and every level of society affecting a healing shift in how we relate to one another and the earth…. Copper Beech Institute strives to awaken us to the fullness of our potential.”

In December, Central Connecticut State University (CCSU) hosted a two-day mindfulness conference, organized by Rosen and three others. The event brought together CREC educators and CCSU professors, as well as psychologists, students and guest speakers.

“There’s more going on in this realm than any individual knew about,” Rosen said. “We just found a lot of people doing interesting work.”

The conference was so successful that Rosen and the team have been asked to host a second. “We’re trying to make the next conference a little more in-depth…whether you’re new to mindfulness or you’re a psychologist and you’re already using these tools and looking to learn more,” she said.

Hartford Hospital has also gotten involved in the mindfulness movement by hosting eight-week Mindfulness-Based-Stress Reduction (MBSR) courses intended to teach the basics of meditation, yoga and stress management.

The series is based on similar courses hosted by the University of Massachusetts Medical School’s Center for Mindfulness and features Jon Kabat-Zinn’s MBSR approach.

Kabat-Zinn established MBSR in the 1970s to help patients who were experiencing chronic pain, and in 2012, he spoke to Google employees about the method.

Today, Google’s “emotional intelligence” initiative is the more progressive type, offering employees access to about a dozen courses on mindfulness meditation and boasting a six-month wait list for its most popular class, “Search Inside Yourself.”

In contrast, Connecticut’s Pratt & Whitney, a Fortune 500 company that manufactures jet engines, hails from a more conservative culture, through which Berard said “the glorification of busy” often permeates.

Berard said the Pratt & Whitney culture fosters hard work, but “just because I’m busy doesn’t mean that I’m doing well or getting anything done.” She understands the importance of retention and keeping employees happy.

Since becoming chair of the Military Engines Health and Wellness Committee, Berard has made it her mission to develop a mindfulness initiative that will create “opportunity areas” for employees to improve both inside and outside of the work environment.

She received support from the president of Pratt & Whitney’s military engines division in establishing “meeting-free afternoons” after 2 p.m. on Fridays.

“Each person and meeting room in Microsoft Outlook now has a block on the calendar to dedicate time for personal development, organization, training and closing out the week and preparing for the next,” she wrote in a graduate admissions essay about her work.

In addition, Berard has held a handful of hour-long mindfulness seminars, ran a health fair and initiated the addition of outdoor seating to Pratt & Whitney’s East Hartford campus.

She has also encouraged “walking meetings” and outdoor meetings to increase blood circulation and foster creativity and has supported mindfulness efforts by UTC-4-Vets, an internal employee resource group for those who have served in the armed forces.

Overall, Berard said she is striving to create a culture of work-life integration. “I always say that when you hire a person, you hire the entire person. You hire people who have interests, hobbies, families, health concerns — and as a company we need to focus on our people,” she wrote in her essay.

For those who may be intimidated by the idea of practicing mindfulness, Berard and Rosen emphasized that no one person is an expert, and no two people are “mindful” in the same way. “It’s a personal practice thing,” Rosen said. “It doesn’t really have to do with career, specifically. It’s not just for people in the healthcare field.”

More importantly, they said, mindfulness is about being able to understand and regulate one’s own emotions, becoming self-aware, developing healthy, life-long survival skills and embracing the present moment.

“Can you really dedicate yourself fully to anything that you’re doing other than what you’re doing right now? The answer is no,” Berard said. “You really need to make time for yourself or else time is going to eat you.”

Melissa Sirois is a senior journalism major at Quinnipiac University. She is writing about public health this spring. She can be reached at melissa.sirois@quinnipiac.edu.

Want to use this story in your publication? We welcome it.

“Watching the people drive by, I used to sit in my office looking out the window and just think, ‘what a country,’” Beaucejour said. “When I came to this country, and I saw the wealth of America, I remembered what I left behind. I saw the America that was spoiled. I used to just think ‘no, this can’t be possible.’”

“Watching the people drive by, I used to sit in my office looking out the window and just think, ‘what a country,’” Beaucejour said. “When I came to this country, and I saw the wealth of America, I remembered what I left behind. I saw the America that was spoiled. I used to just think ‘no, this can’t be possible.’”

But it’s not the extra hours at the library that have got her speaking so passionately—at least, not this time. It’s the issue of the current state of sexual education curriculum in Connecticut.

But it’s not the extra hours at the library that have got her speaking so passionately—at least, not this time. It’s the issue of the current state of sexual education curriculum in Connecticut.